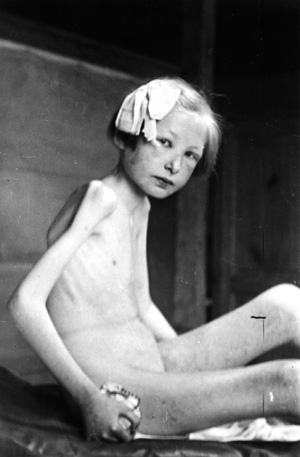

Yours from a "Christian" nation...

Hoover Institution Archives

In

the largest episode of forced migration in history, millions of

German-speaking civilians were sent to Germany from Czechoslovakia

(above) and other European countries after World War II by order of the

United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union.

Finally he located the source of the screams, a pregnant woman who had gone into premature labor and was hemorrhaging profusely. When he attempted to move her from where she lay into a more comfortable position, he found that "she was frozen to the floor with her own blood." Other than temporarily stanching the bleeding, Loch was unable to do anything to help her, and he never learned whether she had lived or died. When the train made its first stop, after more than four days in transit, 16 frost-covered corpses were pulled from the wagons before the remaining deportees were put back on board to continue their journey. A further 42 passengers would later succumb to the effects of their ordeal, among them Loch's wife.

Hoover Institution Archives

An

estimated 500,000 people died in the course of the organized expulsions;

survivors were left in Allied-occupied Germany to fend for themselves.

What was different about the deportation of Loch and his fellow passengers, however, was that it took place by order of the United States and Britain as well as the Soviet Union, nearly two years after the declaration of peace.

Between 1945 and 1950, Europe witnessed the largest episode of forced migration, and perhaps the single greatest movement of population, in human history. Between 12 million and 14 million German-speaking civilians—the overwhelming majority of whom were women, old people, and children under 16—were forcibly ejected from their places of birth in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, and what are today the western districts of Poland. As The New York Times noted in December 1945, the number of people the Allies proposed to transfer in just a few months was about the same as the total number of all the immigrants admitted to the United States since the beginning of the 20th century. They were deposited among the ruins of Allied-occupied Germany to fend for themselves as best they could. The number who died as a result of starvation, disease, beatings, or outright execution is unknown, but conservative estimates suggest that at least 500,000 people lost their lives in the course of the operation.

Most disturbingly of all, tens of thousands perished as a result of ill treatment while being used as slave labor (or, in the Allies' cynical formulation, "reparations in kind") in a vast network of camps extending across central and southeastern Europe—many of which, like Auschwitz I and Theresienstadt, were former German concentration camps kept in operation for years after the war. As Sir John Colville, formerly Winston Churchill's private secretary, told his colleagues in the British Foreign Office in 1946, it was clear that "concentration camps and all they stand for did not come to an end with the defeat of Germany." Ironically, no more than 100 or so miles away from the camps being put to this new use, the surviving Nazi leaders were being tried by the Allies in the courtroom at Nuremberg on a bill of indictment that listed "deportation and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population" under the heading of "crimes against humanity."

By any measure, the postwar expulsions were a manmade disaster and one of the most significant examples of the mass violation of human rights in recent history. Yet although they occurred within living memory, in time of peace, and in the middle of the world's most densely populated continent, they remain all but unknown outside Germany itself. On the rare occasions that they rate more than a footnote in European-history textbooks, they are commonly depicted as justified retribution for Nazi Germany's wartime atrocities or a painful but necessary expedient to ensure the future peace of Europe. As the historian Richard J. Evans asserted in In Hitler's Shadow (1989) the decision to purge the continent of its German-speaking minorities remains "defensible" in light of the Holocaust and has shown itself to be a successful experiment in "defusing ethnic antagonisms through the mass transfer of populations."

Even at the time, not everyone agreed. George Orwell, an outspoken opponent of the expulsions, pointed out in his essay "Politics and the English Language" that the expression "transfer of population" was one of a number of euphemisms whose purpose was "largely the defense of the indefensible." The philosopher Bertrand Russell acidly inquired: "Are mass deportations crimes when committed by our enemies during war and justifiable measures of social adjustment when carried out by our allies in time of peace?" A still more uncomfortable observation was made by the left-wing publisher Victor Gollancz, who reasoned that "if every German was indeed responsible for what happened at Belsen, then we, as members of a democratic country and not a fascist one with no free press or parliament, were responsible individually as well as collectively" for what was being done to noncombatants in the Allies' name.

That the expulsions would inevitably cause death and hardship on a very large scale had been fully recognized by those who set them in motion. To a considerable extent, they were counting on it. For the expelling countries—especially Czechoslovakia and Poland—the use of terror against their German-speaking populations was intended not simply as revenge for their wartime victimization, but also as a means of triggering a mass stampede across the borders and finally achieving their governments' prewar ambition to create ethnically homogeneous nation-states. (Before 1939, less than two-thirds of Poland's population, and only a slightly larger proportion of Czechoslovakia's, consisted of gentile Poles, Czechs, or Slovaks.)... Finish reading @Source The Chronicle