And how he got three years in jail.

Should have partnered-up with a banker. He'd still be 'practicing'.

Should have partnered-up with a banker. He'd still be 'practicing'.

An early review of the book noted this warning didn't seem to fit with the tone of the text, which repeatedly implied "that uncapping, MAC [Media Access Control] cloning, and evading detection is a noble pursuit." (Though one section did include "recommendations to ISP engineers on how to improve their systems to more easily defeat and detect cable modem hackers.")

The feds weren't buying the "research" angle, either; they were convinced that DerEngel was running the country's largest cable modem hacking operation, showing thousands of people around the country how to get free or higher-speed service from local Internet providers. And they were going to stop it.

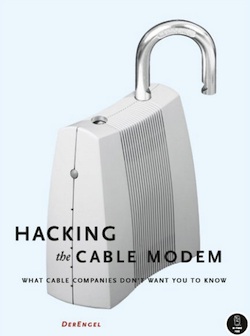

Hacking modem

|

| Harris' book on cable modem hacking |

The tools came in two basic varieties: a packet sniffer dubbed "CoaxThief" and a MAC address/config file changer for select cable modems. Together, the tools enabled some fairly clever Internet fraud.

To understand how it worked, consider how cable modems function. Cable networks generally use a shared line connecting many homes in a single neighborhood, as opposed to DSL, where each home's line runs all the way back to a central phone office. That posed a problem for cable operators when they began offering Internet access: how do you tell which traffic on the wire is being paid for by customers, and how do you limit them to their subscribed speed tier?

The basic mechanism involved MAC controls. Each cable modem had a unique MAC address linked to a subscriber's account, so the cable headend could simply block all traffic that didn't originate from a MAC address linked to a paid-up account. Problem solved!

But not completely, because computers are notoriously flexible. Intrepid hackers quickly figured out tricks to rewrite their MAC addresses, using ones associated with paying customers. Bam—free Internet.

Of course, there was a hitch. Cable companies, though widely loathed, are not in fact staffed only with zombified morons. They had a further limitation in place on local lines: two identical MAC addresses couldn't exist on a single neighborhood segment, to prevent exactly this sort of fraud.

So the hackers had to get social. Using tools like CoaxThief, they could sniff their local cable lines for the MAC addresses of other users, but they couldn't use the addresses themselves. Instead, they went online—to forums like those on TCNiSO.net—and they swapped with others who had done the same thing. Now the two hackers involved in the swap had a MAC address that came from outside their neighborhood. They just had to get it into the modem, which was designed to prevent such tampering.

That's where Harris's other software came in. Released in 2003, the Sigma firmware exploited modem vulnerabilities to install itself into a modem's memory, allowing users to change the device's MAC addresses. The code had to stay continuously up-to-date, since cable companies regularly tweaked their own countermeasures in response. In 2005, for instance, Sigma became SigmaX and gained the ability to defeat cable-company initiated "probes" of cable modems on their lines.

SigmaX changelog; note "config file changer" and "MAC address changer"

With the right MAC address and the right software, suddenly the hacked cable modem provided a connection to the cable system. And it could get even faster. Cable modems use cable-provided profiles to limit users to specific speed tiers; Harris also found ways to uncap the modems by altering these profiles, upping their speeds dramatically.

Despite the talk about "diagnostic purposes," the TCNiSO.net operation doesn't come across as a particularly subtle operation. Harris employed several people around the country to code his apps and firmware, and he oversaw a forum in which people offered troubleshooting advice on stealing Internet service and on exchanging MAC addresses. (One thread in 2006 was called "What i need to do, so my isp can't catch me." Others offered "the Charter 0/0 config for download," while another asked: "RR [RoadRuner] in North Carolina, anyone want to trade macs?") An FBI agent had no trouble calling the phone number for TCNiSO and ordering a hacked modem...