|

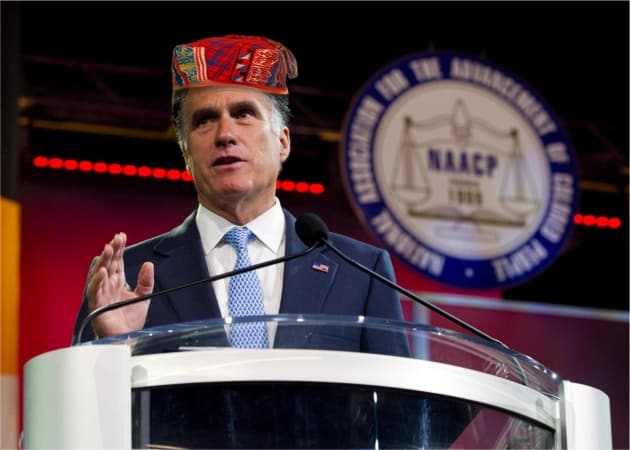

| HOUSTON (TheSkunk.org) — In a speech Wednesday (7/11/12) to the annual NAACP leadership convention, Mitt Romney opened by greeting the crowd with the phrase “Hakuna Matada.” The audience reacted with curious bewilderment, as the presumptive Republican presidential nominee smiled and gave the “thumbs up” sign. |

Scanned & Published from the series by ChasVoice

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE (NAACP)

From The Biographical Dictionary of the Left by Francis X. Gannon, 1969

"The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremist folly, and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than of artificial forcing. No race that has anything to contribute to the markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized. It is important and right that all privileges of the law be ours, but it is vastly more important that we be prepared for the exercises of these privileges. The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera-house." These were the words of Booker T. Washington- Negro educator, a native Virginian born in slavery, and founder of Tuskegee Institute.

Throughout his adult life, Washington labored to impress upon Negroes that they would have a rewarding role in America's progress if only they developed industrial and agricultural skills through vocational training in a massive "self-help" program among Negroes. From the whites Washington asked for cooperation and understanding which would result in "interlacing our industrial, commercial, civil, and religious life with yours in a way that shall make the interests of both races one. In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress." There were Negro intellectuals who disagreed sharply with Washington. They alleged that Washington was leading his fellow Negroes into a surrender of political rights and a permanent system of social segregation.

The most prominent among the anti-Washington Negroes was W. E. Burghardt DuBois - a native of Massachusetts with a doctorate and two lesser degrees from Harvard. (DuBois, before the turn of the century, was a Stalinist. Later, he formally joined the Socialist Party, resigned and became an active fellow traveler of the Reds, and eventually became a member of the Communist Party. And, today his name is memorialized in the Communists' DuBois Clubs.)

In a total misrepresentation of Washington's views, DuBois said:

"Mr. Washington apologizes for injustice, North and South, does not rightly value the privilege and duty of voting, belittles the emasculating effects of caste distinctions, and opposes the higher training and ambition of our brighter minds... [therefore] we must unceasingly and firmly oppose him."

To offset Washington's "self-help" program, DuBois - in 1905 -and a group of collectivists founded the Niagara Movement. DuBois planned, as an immediate goal, to train a Negro elite - "the Talented Tenth" - which could lead the Negro masses in a militant program to agitate for unconditional political and social equality.

Out of the Niagara Movement, there emerged - in 1909 - the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People with its announced purposes: "To promote equality of rights and eradicate caste or race prejudice among the citizens of the United States; to advance the interest of colored citizens; to secure for them impartial suffrage; and to increase their opportunities for securing justice in the courts, education for their children, employment according to their ability, and complete equality before the law."

The formation of the NAACP was urged by the leading radicals of the era including Jane Addams, John Dewey, William Lloyd Garrison, John Haynes Holmes, Lincoln Steffens, Brand Whitlock, Lillian Wald, Rabbi Stephen Wise, and Ray Stannard Baker. Among the first officials of the NAACP were more radicals including: Mary White Ovington, Oswald Garrison Vilard, Walter E. Sachs, John Milholland, Frances Blascoer, and William English Walling. Other radicals were among the first NAACP members: Florence Kelly, William Pickens, James W. Johnson, Charles E. Russell, and E. R. A. Seligman. (Many of these individuals were already or would soon become enrolled in the newly formed Intercollegiate Socialist Society [which later became the League for Industrial Democracy] and, within a few years, they were prominent in various pacifist groups, including the Fellowship of Reconciliation, and the American Civil Liberties Union. The NAACP gave them one more vantage point - agitation for Negroes' equality - from which they could promote Socialism and other facets of radicalism.)

Moorfield Storey, a white attorney from Boston, was the first president of the NAACP. DuBois became the organization's first director of publicity and research and the editor of the organization's monthly magazine, The Crisis. For twenty-four years, The Crisis served as DuBois' regular outlet for unbridled racism. In one of his editorials, he set the tone for the magazine when he wrote that "the most ordinary Negro is a distinct gentleman, but it takes extraordinary training and opportunity to make the average white man anything but a hog."

From 1909 until 1934, DuBois - in this country and abroad - was the most prominent spokesman for the NAACP. In that same period, Mary White Ovington, a white social worker and an official of the organization, was second only to DuBois in propaganda efforts for the organization. The NAACP has also been fortunate in having three very able men serve as executive secretary: James Weldon Johnson (1920-1928), Walter White (1929-1955), and Roy Wilkins since 1955. Wilkins also was editor of The Crisis from 1934 until 1949. Long tenure in office has also been characteristic of the NAACP's presidents - all white men: Moorfield Story (1910-1915), Joel Spingarn (1915-1940), Arthur Spingarn (1940-1966), and, since 1966, Kivie Kaplan.

During its first year, the NAACP recruited 329 members. At the end of twenty years, there were 88,000 members. The peak of membership was reached in 1963 with 510,000 and, at the end of 1968, there were 449,000 members.

In its early history, the NAACP proved to be a natural attraction for Communists. DuBois, the real leader of the organization, "hailed the Russian Revolution of 1917," and he traveled to the Soviet Union in 1926 and 1936. He especially liked "the racial attitudes of the Communists."

In 1920, the question of the Negro in America had been discussed at the second world congress of the Communist International. At that time, the Negro in America was described as a "national" minority rather than a "racial" minority.

By 1922, the Communists in America had received their orders from the Communist International to exploit Negroes in the Communist program against the peace and security of the United States. In 1923, the NAACP began to receive grants from the Garland Fund which was a major source for the financing of Communist Party enterprises. (Officials of the Fund included Communists William Z. Foster, Benjamin Gitlow, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Scott Nearing, and Robert W. Dunn, along with prominent leftwingers Roger Baldwin, Sidney Hillman, Ernest Gruening, Morris Ernst, Mary E. McDowell, Harry F. Ward, Judah L. Magnes, Freda Kirchwey, Emanuel Celler, Paul H. Douglas, Moorfield Storey, and Oswald Garrison Vilard.) The grants continued until, at least, 1934.

There could be no doubt that the NAACP was of particular interest to the Communist Party. At the fourth national convention of the Workers (Communist) Party in 1925, the comrades were told that it was "permissible and necessary for selected Communists (not the party membership as a whole) to enter its [NAACP's] conventions and to make proposals calculated to enlighten the Negro masses under its influence as to the nature and necessity of the class struggle, the identity of their exploiters - - .

In 1928, the Communist International instructed American Negro Communists to work for a Negro-controlled State composed of all contiguous Southern countries having majority black populations - the so-called Black Belt. In 1930, the Communist International instructed the entire Communist Party, USA to organize the Negroes of the South for the purpose of setting up a separate state and government in the South.

The noted Negro journalist George Schuyler, who was familiar with the personnel and operations of the NAACP, has written of this era:

"This was the time the veteran Socialist, Dr. W. E. B. Dubois (then the acknowledged intellectual leader of Aframerica, and editor of The Crisis since 1910), wrote an editorial in January 1934 to plug for segregation. He declared that 'the thinking colored people of the United States must stop being stampeded by the word segregation.' With considerable exaggeration, he held that segregation was 'more insistent, more prevalent and more unassailable by appeal and argument' than ever before; that Negroes must 'fight segregation with segregation,' and he told them to 'voluntarily and insistently organize our economic and social power no matter how much segregation is involved.' This shocked the NAACP directors. But, DuBois continued to urge that Negroes 'cut intercourse with white Americans to the minimum demanded by decent living." (Mr. Schuyler's observations appeared in The Review of the News, December 18, 1968.)

DuBois' views, so overtly compatible with the Communists' plans for a segregated Negro America, were an embarrassment to the NAACP which, of necessity, had to depend upon financial and other support from white America. And, in 1934, DuBois separated from the NAACP. (He returned ten years later but within four years he left the NAACP permanently and devoted his energies full-time working for Communist projects.)

NAACP founder WEB Du Bois' Commitment to Communism and Socialism

In a rare interview, David Du Bois, son of NAACP founding member W.E.B. Du Bois, speaks passionately of his dad's commitment to Communism and Socialism, and how his wife introduced him to leading white activists within the Progressive movement at that time, among other things.

The departure of DuBois from the NAACP did not mean that the organization was averse to Communists. George Schuyler has narrated:

"Meanwhile, the Association [NAACP] was playing patsy with the forces of the Left . . . and were thereby floating on financial beds of ease. Evil associations corrupt good manners, and also good sense. As the Communists, crypto Communists and fellow travelers moved in on the New Deal and took charge, the NAACP was more and more affected. The indefatigable Walter F. White, NAACP executive secretary, was weekly in Washington cultivating white power which was often Red. Then the New York Communist organizers, Manning Johnson and Leonard Patterson, traveled to Washington, contacted the Red faculty members at Howard University, and 'sold' them on organizing an activist National Negro Congress (NNC). Among the first suckered into it was the NAACP's executive secretary. This committed the Association to supporting an outfit tailored originally by the Communist Party of the U.S.A. to destroy it." (The NAACP's affiliation with the National Negro Congress was not an isolated tie-in with the Communists. In 1938, the NAACP was represented in the World Youth Congress, a Communist enterprise. And, in the 1940's the NAACP was affiliated with American Youth for a Free World, the American affiliate of the World Federation of Democratic Youth, a Communist clearing house.)

As was the case with so many Communist fronts, the National Negro Congress foundered amidst the confusion of the Hitler-Stalin Pact.

The National Negro Congress, however, had a short-lived revival. George Schuyler recounted: "With War's end and the return of the Communist Party to its pre-War line (crying for 'Self-Determination for the Black Belt' and trying to invade the province of the NAACP with the hastily-organized Civil Rights Congress), there was no difficulty in getting high Association officials to join. Soon the National Negro Congress, in one of its last gasps, presented a petition to the United Nations charging the United States with genocide on its Negro population - which, curiously, had increased since 1790 to 1940 from 750,000 to 15 million. Not to be outdone, Dr. DuBois, who had again been given executive office by the NAACP, the following year presented a similar petition charging American genocide against the Negroes. It followed the general line of the Communist plea, and Walter White and DuBois traipsed out to Lake Success to present it."

One of the NAACP's most literate apologists was the late Langston Hughes. (From 1925 until his death in 1967, Hughes was openly associated with Communist Party projects and enterprises. In 1956, the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee included Hughes in its list of eighty-two names of the most active and typical sponsors of Communist front organizations. In sworn testimony, former Communist Party functionary Manning Johnson identified Hughes as a member of the Communist Party as of December, 1935.)

In 1962, Hughes wrote Fight for Freedom: The Story of the NAACP. In his book, Hughes said: "Attempts to label the NAACP subversive, Communist-influenced, or out-and-out Communist have continued for a long time. The late Negro professional witness, ex-Communist Manning Johnson, since discredited, testified before two southern legislative committees to the effect that the NAACP was 'a vehicle of the Communist Party designed to overthrow the government of the United States." [Johnson was not a professional witness but a genuinely repentant American who, from his years as a top Negro Communist, testified accurately before, and cooperated fully with, federal and state investigating committees and agencies. He was discredited only by the Communist Party, its fellow travelers, and its dupes. He did identify Hughes as a Communist. He did testify as to the Communist character of the NAACP since he had been assigned the job of bringing Negro organizations into the Communist orbit.)

Hughes, however, in his whitewash of the NAACP (which, by the way, had conferred its highest award - the Spingarn Medal - upon him in 1960), wrote: "Utterly disregarding the truth, these malicious and irresponsible accusations ignore evidence, so clearly on the record, that the NAACP is not and was not Communist and has never even remotely been under Communist influence. Since its earliest years, its top officials from Joel Spingarn and James Weldon Johnson to Walter White and Roy Wilkins have attacked communism in no uncertain terms in both speaking and writing [and] until recently, the official Communist program for Negroes called for the establishment of a separate Negro nation, an idea that was directly opposite to the NAACP's philosophy of integration." (Spingarn and Johnson were officials when the NAACP was receiving grants from the Garland Fund, the outfit which was created to finance Communist enterprises. White, as George Schuyler noted, worked hand-in-hand with the Communists. Wilkins, on the NAACP's staff since 1931, went out of his way to praise the Communist Party for the help it gave to the Negroes. And, from 1937 until 1949, Wilkins was affiliated with a number of Communist fronts and enterprises. He did become somewhat discreet after 1949 [in 1949 and 1950, he was acting executive secretary and, since 1955, he has been the executive secretary of the NAACP] but in 1965 he joined with notorious Communist leaders to memorialize the deceased Communist W. E. B. DuBois. And, Hughes conveniently forgot that the Communists and the NAACP set aside temporarily the idea of a separate Negro nation only because American Negro masses simply showed no interest in such segregation.)

It is true that from time to time the NAACP went through the motions of denouncing Communism and Communists but, at the same time, the NAACP harbored in its roster of officials and in its membership a legion of Communist-fronters, individuals whose prestige and influence made their presence in the fronts of far more importance to the Communist Party than if they were dues-paying members of obscure and secretive party cells. Among these individuals who represented every Communist front, project, and enterprise ever to appear in this country have been: Roger N. Baldwin, George S. Counts, J. Frank Dobie, Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Arthur Garfield Hays, Freda Kirchwey, Alfred Baker Lewis, Archibald MacLeish, Reinhold Niebuhr, A. Philip Randolph, Guy Emery Shipler, Lillian Smith, Norman Thomas, Leonard Bernstein, Eugene Carson Blake, Sarah Gibson Blanding, Ralph Bunche, Morris Ernst, Buell Gallagher, Rabbi Roland Gittelsohn, Frank Graham, Bishop James A. Pike, Carl Rowan, Eleanor Roosevelt, Walter Reuther, Channing Tobias, Algernon D. Black, Bishop G. Bromley Oxnam, Van Wyck Brooks, Henry Hitt Crane, Benjamin E. Mays, S. Ralph Harlow, and Oscar Hammerstein II. Hughes even boasted that the NAACP membership included Jawaharlal Nehru of India, Averell Harriman, Herbert Lehman, Harry Golden, Harry Belafonte, G. Mennen Williams, Chester Bowles, Nelson Rockefeller, Alan Paton, and Adam Clayton Powell - none of whom could be considered as anything less than extremely soft on Communism. Even after the publication of Hughes' book, there appeared on NAACP letterheads such names as Walter Gellhorn, Telford Taylor, William Sloane Coffin Jr., Dick Gregory, Ossie Davis, Steve Allen, Ruby Dee, Aaron Copland, Helen Buttenwieser, Erwin N. Griswold, Senator Edward M. Kennedy, John A. Volpe, Kirtley Mather, Elliot L. Richardson, and Henry Cabot Lodge.

Among those honored by the NAACP with its annual Spingam Medal have been:

W. E. B. DuBois, Mary McLeod Bethune, A. Philip Randolph, William Hastie, Paul Robeson, Thurgood Marshall, Richard Wright, Martin L. King Jr., Ralph Bunche, Walter White, and Langston Hughes.

From its inception to the present, no matter the protestations of Langston Hughes or any other NAACP apologist, the organization's officials and its known members, collectively and individually, have represented the influential left, the leadership of Communist fronts and left-wing political and pacifist groups, and the most effective of the anti-anti-Communist establishment.

In 1946, the NAACP cooperated with the Communist Party as the latter, in one of its most ambitious political projects of all time, established the Progressive Citizens of America - the basis for Henry Wallace's Communist-dominated Progressive Party in the presidential election of 1948. In 1951, when the Massachusetts legislature was considering a bill to outlaw the Communist Party, the Boston branch of the NAACP, through its legislation committee, opposed the bill. The Committee's chairman, Edward W. Brooke (now U.S. Senator), argued that the bill was "against democratic principles and endangers American civil liberties."

The Communists in the United States have certainly recognized the value of the NAACP as an ally. In 1950, Communist leader Robert Thompson boasted: "The emergence of a powerful left, anti-imperialist, anti-fascist current among the Negro people is unmistakable and is clearly discernible in the NAACP. This Left, anti-imperialist trend in the Association insists upon much greater attention by the organization to the pressing economic and political problems facing the Negro masses." (Political Affairs, February, 1950.)

In 1953, an unusual and total endorsement was given to the NAACP by the Communists in their Daily Worker (September 30): "It should be clear that we Communists are the first to insist that the labor movement, all sections of it, should give every possible support to any and all campaigns conducted by the NAACP."

Four years later, a similar endorsement appeared in the Daily Worker (February 19, 1957): "Communists in labor unions are thus pledged to get their unions to support the NAACP, to better express the affiance of labor with the Negro people. Communists in communities are pledged to aid in increasing the membership and financial strength of the NAACP, whether as members or not."

The relationship between the NAACP and the Communist Party has been demonstrable through the activities of those attorneys who have held office in the NAACP, its branches, or the "Committee of 100" which supports the NAACP's Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

Among the more prominent attorneys associated with the NAACP have been Morris Ernst, Robert W. Kenny, Earl B. Dickerson, Clarence Darrow, Bartley Crum, Osmond Fraenkel, Hubert Delany, and Loren Miller - all of whom had an unusual affinity for Communist fronts and projects. For ten years prior to his appointment in 1939 to the Supreme Court of the United States, Felix Frankfurter, an unreconstricted Bolshevik, served as a legal adviser to the NAACP. That intimate association never deterred Frankfurter from sitting and writing decisions on cases where the NAACP was directly involved. But, in its entire history, the NAACP owes its most dramatic successes to the work of Thurgood Marshall. From 1936 until 1961, he was with the NAACP as assistant special counsel (1936-1938), special counsels (1938-1940), and director and counsel for the Legal Defense and Educational Fund (1940-1961). [In 1962, Marshall was appointed by President Kennedy to be U.S. Circuit Court Justice for the Second Judicial Circuit; in 1965, President Johnson appointed him to be Solicitor General of the United States; and, in 1967, President Johnson appointed him to the Supreme Court of the United States.]

From 1938 to 1961, Marshall represented the NAACP thirty-two times before the Supreme Court. He won twenty-nine of the cases. His most notable achievement before the Supreme Court came in 1954, when he successfully argued the Brown v. Board of Education case with the resultant revolutionary decision by the Court that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. There were circumstances, however, which dulled Marshall's victory and the Court's decision.

Seven years after Brown v. Board of Education, Dr. Alfred H. Kelly, an historian who served as an aide to Marshall in the preparation of a brief for the case, revealed that Marshall set out to deceive the Court with dishonest historical arguments. In an address to the American Historical Association, Dr. Kelly told how he was asked by Marshall "to prepare a research paper on the intent of the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment with respect to the constitutionality of racially segregated schools."

Dr. Kelly then described his research efforts: "As a constitutional historian, I knew, of course, that the Fourteenth Amendment had evolved, in some considerable part, out of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Accordingly, I went to work on the 1866 volumes of the 'Congressional Globe,' reading anew the story of the debates that winter and spring for clues concerning the intent which [Lyman] Trumbell, [John A.J Bingham, [Thaddeus] Stevens and the other congressional Radicals might have had with respect to legalized segregation in particular.

"I did not really expect to find very much of anything

"As any reasonably competent historian could have told the Court and the lawyers on both sides, the historical questions they had framed [in 1953] did not necessarily have very much relevance at all to the issues that seemed consequential then to the embattled Radicals who had hammered out the Civil Rights Act and the Fourteenth Amendment that spring of 1866 ...

"To my surprise, the debates reprinted in the 1866 volumes of the 'Globe' had a good deal to say about school segregation. Unhappily, from the NAACP's point of view, most of what appeared there at first blush looked rather decidedly bad....

"The conclusion for any reasonably objective historian was painfully clear. The Civil Rights Act as it passed Congress was specifically rewritten to avoid the embarrassing question of a congressional attack upon State racial-segregation laws, including school segregation. .

"The paper I prepared for the September conference [with Mr. Marshall in 1953] was not adequate by any standard. I was trying to be both historian and advocate within the same paper, and the combination, as I found out, was not a very good one.

"I was facing, for the first time in my own career, the deadly opposition between my professional integrity as a historian and my wishes and hopes with respect to a contemporary question of values, of ideals, of policy, of partisanship and of political objectives. I suppose if a man is without scruple, this matter will not bother him, but I am frank to say that it bothered me terribly . . .

Dr. Kelly's work, however, was not completed. He was recalled for help by Marshall, and, along with Robert Ming Jr., a former law professor at Howard University and the University of Chicago, Kelly drafted a brief for Marshall to present to the Supreme Court. And thus began an extraordinary marriage of phony history and highly questionable legal ethics: "I am very much afraid that for the next few days I ceased to function as a historian, and, instead, took up the practice of law without a license. The problem we faced was not the historian's discovery of the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth; the problem instead was the formulation of an adequate gloss on the fateful events of 1866 sufficient to convince the Court that we had something of a historical case . . . -

While the NAACP has expended much of its finances and energies upon the support of the demonstrative groups, it has not forsaken its other projects. It continues to agitate for government housing and government "created" jobs for Negroes; for socialized medicine; for forcible integration of public schools; for federal interference with state voting laws, and, for federal interference with intrastate travel laws. In other projects, the NAACP has campaigned against the House Committee on Un-American Activities, against Barry Goldwater, against South Africa, for the peace corps, and for the United Nations.

In July, 1968, in an advertisement in Esquire magazine, the NAACP seemed to revert to the racism that had been characteristic of W. E. B. DuBois. In the ad, the NAACP charged that "white America denies black America its constitutional rights. White America creates the ghetto and slams the door on efforts to escape. White America traps the Negro in a cycle of prejudice and poverty that denies his humanity and destroys his dignity." Meanwhile, the NAACP was holding its fifty-ninth annual convention.

At the six-day convention in June, 1968, the delegates worked on the theme: "the building of economic and political power within the nation's ghettoes." A group of NAACP officials and leaders, organized as the National Committee to Revitalize the NAACP Movement, were obviously disturbed at the organization's loss of influence in the black community because of the rising popularity of black militant groups. These Leaders said: "We must rid ourselves of a solely middle-class image and organize our black stakeless and hopeless; the down and out, the inferiority complex-ridden." They also expressed their shock at "the thundering silence of the association's top leadership on issues of concern to black people."

The remedies suggested by the leaders to restore confidence in the NAACP included the formation of a black-oriented political bloc, similar to labor and farmer blocs; lobbying for more federal handouts for blacks, especially through a guaranteed annual wage plan; and, the introduction into more schools of a "black history" program in an effort "to restore a lost sense of pride and self-worth."

The trouble in the ranks of the NAACP continued after the annual convention. In October 1968, a lawyer on the NAACP staff wrote an article for the New York Times magazine - He was bitterly critical of the Supreme Court for not doing more for Negroes. The utter ridiculousness of the article caused the lawyer to be fired, to protest his firing.