Educational codicil for early Europe and their monetary crises.

The great German hyperinflation of 1923 is passing out of living memory now, but it has not been entirely forgotten. Indeed, you don’t have to go too far to hear it cited as a terrible example of what can happen when a government lets the economy spin out of control.

At its peak in the autumn of that year, inflation in the Weimar Republic hit 325,000,000 percent, while the exchange rate plummeted from 9 marks to 4.2 billion marks to the dollar; when thieves robbed one worker who had used a wheelbarrow to cart off the billions of marks that were his week’s wages, they stole the wheelbarrow but left the useless wads of cash piled on the curb. A famous photo taken in this period shows a German housewife firing her boiler with an imposing pile of worthless notes.

Easy though it is to think of 1923 as a uniquely terrible episode, though, the truth is that it was not. It was not even the worst of the 20th century; during its Hungarian equivalent, in 1945-46, prices doubled every 15 hours, and at the peak of this crisis, the Hungarian government was forced to announce the latest inflation rate via radio each morning–so workers could negotiate a new pay scale with their bosses—and issue the largest-denomination bank note ever to be legal tender: the 100 quintillion (1020) pengo note.

When the debased currency was finally withdrawn, the total value of all the cash then in circulation in the country was reckoned at 1/10th of a cent. Nor was 1923 even the first time that Germany had experienced an uncontrollable rise in prices. It had also happened long before, in the early years of the 17th century. And that hyperinflation (which is generally known by its evocative German name, the kipper- und wipperzeit) was a lot stranger than what happened in 1923. In fact, it remains arguably the most bizarre episode in all of economic history.

What made the kipper- und wipperzeit so incredible was that it was the product not only of slipshod economic management, but also of deliberate attempts by a large number of German states to systematically defraud their neighbors. This monetary terrorism had its roots in the economic problems of the late 16th century and lasted long enough to merge into the general crisis of the 1620s caused by the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War, which killed roughly 20 percent of the population of Germany. While it lasted, the madness infected large swaths of German-speaking Europe, from the Swiss Alps to the Baltic coast, and it resulted in some surreal scenes: Bishops took over nunneries and turned them into makeshift mints, the better to pump out debased coinage; princes indulged in the tit-for-tat unleashing of hordes of crooked money-changers, who crossed into neighboring territories equipped with mobile bureaux de change, bags full of dodgy money, and a roving commission to seek out gullible peasants who would swap their good money for bad.

By the time it stuttered to a halt, the kipper- und wipperzeit had undermined economies as far apart as Britain and Muscovy, and—just as in 1923—it was possible to tell how badly things were going from the sight of children playing in the streets with piles of worthless currency.

The economies of Europe had already been destabilized by a flood of precious metals from the New World (where in 1540 the Spaniards discovered an entire mountain of silver in Peru) and of copper from the Kopperburg in Sweden. This kick-started a sharp rise in inflation, as any substantial increase in the money supply will. In addition, there were limits to the control that most states had over their coinage. Foreign currency circulated freely in even the largest countries; the economic historian Charles Kindleberger estimates that in Milan, then a small but powerful independent duchy, as many as 50 different, mainly foreign, gold and silver coins were in use. And so a good deal had to be taken on trust; at a time when coins actually were worth something—they were supposed to contain amounts of precious metal equivalent to their stated value—there was always a risk in accepting coins of unknown provenance. The strange currency might turn out to have been clipped (that is, had its edges snipped to produce metal shavings that could then be melted down and turned into more coins); worse, it might have been debased. Contemporary mints, which were often privately owned and operated under license from the state authorities, had yet to invent the milled edge to prevent clipping, and hand-produced coins by stamping them out with dies. In short, the system might have been designed to encourage crooked practice.

This was particularly the case in Germany, which was then not a single state but an unruly hodgepodge of nearly 2,000 more or less independent fragments, ranging in size from quite large kingdoms down to micro-states that could be crossed on foot in an afternoon. Most huddled together under the tattered banner of the Holy Roman Empire, which had once been a great power in Europe, but was by 1600 in disarray. At a time when Berlin was still a provincial town of no real note, the empire was ruled from Vienna by the Hapsburgs, but it had little in the way of central government and its great princes did much as they pleased. A few years later, the whole ramshackle edifice would be famously dismissed, in Voltaire’s phrase, as neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire.

The coins minted in the Empire reflected this barely suppressed chaos. In theory the currency was controlled and harmonized by the terms of the Imperial Mint Ordinance issued at Augsburg in 1559, which specified, on pain of death, that coins could be issued only by a select group of imperial princes via a limited number of mints that were subject to periodic inspections by officials known as Kreiswardeine. In practice, however, the Ordinance was never rigorously enforced, and because it was cost more to mint low-denomination coins than larger ones, the imperial mints soon stopped producing many smaller coins.

Unsurprisingly, this practice soon created strong demand for the coins used in everyday transactions. Consequently, the empire began attracting, and circulating, foreign coins of unknown quality in large quantities, and unauthorized mints known as Heckenmünzen began to spring up like mushrooms after summer rains. As the number of mints in operation rose, demand for silver and copper soared. Coiners soon began to yield to the temptation to debase their coinage, reducing the content of precious metal to the point where the coins were worth substantially less than their face value. Inevitably, inflation began to rise.

Economists have long studied the problems “‘bad” money can cause an economy. The effects were first described by Sir Thomas Gresham (1518-79), an English merchant of Queen Elizabeth’s reign. Gresham is remembered for stating what has become known as “Gresham’s Law”—that the bad money in an economy drives out the good. Put more formally, the law implies that an overvalued currency (such as one in which the stated content of precious metal is much less than expected) will result either in the hoarding of good money (because spending it runs the risk of receiving bad money in change) or in the melting down and recoining of good money to make a larger amount of debased coinage.

What happened in Germany after bad money started to circulate there in about 1600 might have been designed as a case study in Gresham’s Law. Coins were increasingly stripped of their gold, silver and copper content; as a result, the imperial currency, the kreuzer, lost about 20 percent of its value between 1582 and 1609. After that, things began to go seriously wrong.

Continue reading...

March 29, 2012

“Kipper und Wipper”: Rogue Traders, Rogue Princes, Rogue Bishops and the German Financial Meltdown of 1621-23

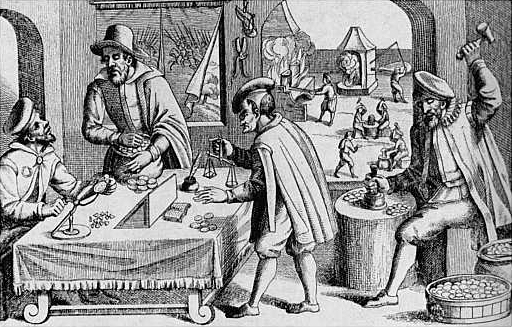

A German mint hard at work producing debased coinage designed to be palmed off on the nearest neighboring state, c.1620

The great German hyperinflation of 1923 is passing out of living memory now, but it has not been entirely forgotten. Indeed, you don’t have to go too far to hear it cited as a terrible example of what can happen when a government lets the economy spin out of control.

At its peak in the autumn of that year, inflation in the Weimar Republic hit 325,000,000 percent, while the exchange rate plummeted from 9 marks to 4.2 billion marks to the dollar; when thieves robbed one worker who had used a wheelbarrow to cart off the billions of marks that were his week’s wages, they stole the wheelbarrow but left the useless wads of cash piled on the curb. A famous photo taken in this period shows a German housewife firing her boiler with an imposing pile of worthless notes.

Easy though it is to think of 1923 as a uniquely terrible episode, though, the truth is that it was not. It was not even the worst of the 20th century; during its Hungarian equivalent, in 1945-46, prices doubled every 15 hours, and at the peak of this crisis, the Hungarian government was forced to announce the latest inflation rate via radio each morning–so workers could negotiate a new pay scale with their bosses—and issue the largest-denomination bank note ever to be legal tender: the 100 quintillion (1020) pengo note.

When the debased currency was finally withdrawn, the total value of all the cash then in circulation in the country was reckoned at 1/10th of a cent. Nor was 1923 even the first time that Germany had experienced an uncontrollable rise in prices. It had also happened long before, in the early years of the 17th century. And that hyperinflation (which is generally known by its evocative German name, the kipper- und wipperzeit) was a lot stranger than what happened in 1923. In fact, it remains arguably the most bizarre episode in all of economic history.

|

| Cheap fuel. A German woman fires her boiler with wads of billion mark notes, autumn 1923. |

By the time it stuttered to a halt, the kipper- und wipperzeit had undermined economies as far apart as Britain and Muscovy, and—just as in 1923—it was possible to tell how badly things were going from the sight of children playing in the streets with piles of worthless currency.

The economies of Europe had already been destabilized by a flood of precious metals from the New World (where in 1540 the Spaniards discovered an entire mountain of silver in Peru) and of copper from the Kopperburg in Sweden. This kick-started a sharp rise in inflation, as any substantial increase in the money supply will. In addition, there were limits to the control that most states had over their coinage. Foreign currency circulated freely in even the largest countries; the economic historian Charles Kindleberger estimates that in Milan, then a small but powerful independent duchy, as many as 50 different, mainly foreign, gold and silver coins were in use. And so a good deal had to be taken on trust; at a time when coins actually were worth something—they were supposed to contain amounts of precious metal equivalent to their stated value—there was always a risk in accepting coins of unknown provenance. The strange currency might turn out to have been clipped (that is, had its edges snipped to produce metal shavings that could then be melted down and turned into more coins); worse, it might have been debased. Contemporary mints, which were often privately owned and operated under license from the state authorities, had yet to invent the milled edge to prevent clipping, and hand-produced coins by stamping them out with dies. In short, the system might have been designed to encourage crooked practice.

|

| A German coin of the kipper- und wipperzeit era, with evidence of clipping on the bottom right. |

Unsurprisingly, this practice soon created strong demand for the coins used in everyday transactions. Consequently, the empire began attracting, and circulating, foreign coins of unknown quality in large quantities, and unauthorized mints known as Heckenmünzen began to spring up like mushrooms after summer rains. As the number of mints in operation rose, demand for silver and copper soared. Coiners soon began to yield to the temptation to debase their coinage, reducing the content of precious metal to the point where the coins were worth substantially less than their face value. Inevitably, inflation began to rise.

|

| Sir Thomas Gresham |

What happened in Germany after bad money started to circulate there in about 1600 might have been designed as a case study in Gresham’s Law. Coins were increasingly stripped of their gold, silver and copper content; as a result, the imperial currency, the kreuzer, lost about 20 percent of its value between 1582 and 1609. After that, things began to go seriously wrong.