May 2, 2013

It's shocking, really. According to ConvergEx Group, "Only 58% of us are even saving for retirement in the first place. Of that group, 60% have less than $25,000 put away ... a full 30% have less than $1,000." According to Nielsen Claritas, Americans age 55 to 64 have a median net worth of $180,000 -- less than they'll likely need for health care spending alone during retirement.

I recently asked Joseph Dear, chief investment officer of CalPERS, one of the world's largest pension funds, whether America was ready for retirement. Without delay, he snapped: "No!"

We have a retirement problem. A very serious one that shouldn't be discounted.

But it is nothing new.

Same as it ever wasThe notion that these challenges are new -- that there was some golden era when Americans were prepared to kick up their feet and enjoy retirement in financial security -- is a myth. By some measures, retirees are in a better position today than at any other time in modern history.

Let's start with something simple. The entire concept of retirement is unique to the late-20th century. Before World War II, most Americans worked until they died.

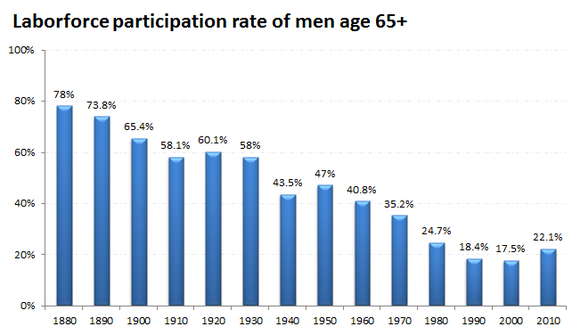

The best way to show this is the labor force participation rate for men age 65 and up:

Source: Economic History Association, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

For most of us, I think the nostalgic sense of America's golden era of retirement is set between the 1950s and the 1990s. That, we often hear, is when workers had pensions and were able to retire with security. But as much as twice the percentage of men were still working into their elderly years back then compared with today.The truth is, the 20th century was brutal for most elderly. As Frederick Lewis Allen writes in his 1950 book The Big Change: "One out of every four families dependent on elderly people and two out of every three single elderly men and women had to get along in 1948 on less than $20 per week [$193 in today's dollars]."

There are a couple of reasons for this. First, those retiring in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, were in their prime earning years during the Great Depression. Not exactly fertile ground for saving.

More importantly, Social Security used to pay out much smaller benefits, even adjusted for inflation.

When Ida Mae Fuller cashed the first Social Security check in 1940, it was for $22.54, or $374 in current dollars. Today, the average monthly benefit in real (inflation-adjusted) terms is more than three times larger. Since payouts are set with a calculation based on wage growth, not just price inflation, real Social Security benefits have risen consistently over the last half-century:

Sources: Annual Statistical Supplement to the Social Security Bulletin, 2012; Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But hold on, I hear you say. Didn't workers have private pensions to rely on in previous decades?Some did, yes. But only a minority. There has never been a time in American history when the majority of retirees took in income from either a private or public pension (outside of Social Security). Nothing close to it, in fact.

Nevin Adams of the Employee Benefit Research Institute tells the story: "Only a quarter of those age 65 or older had pension income in 1975 ... The highest level ever was the early 1990s, when fewer than 4 in 10 (both public- and private-sector workers) reported pension income."

Mr. Adams continues: "In other words, even in the 'good old days' when 'everybody' supposedly had a pension, the reality is that most workers in the private sector did not."

Here's what's really interesting. In 1975, 15% of all income reported by those 65 and older came from pensions, according to Adams. By 2010, that figure actually increased, to 20%.

The bottom line, Adams writes, is that "even when defined benefit pensions were more prevalent than they are today, most Americans still had to worry about retirement income shortfalls."

As a matter of fact, retirees had a lot more to worry about in past decades than they do today.

The Census Bureau's measure of poverty -- based largely on how much of a household's income is devoted to basic food necessities -- for those age 65 and up has plunged since the 1960s, continuing to fall even during the financial crisis:

Source: Census Bureau.

By this metric -- and I struggle to think of a more complete measure of financial wellbeing than poverty -- those age 65 and up have never been in better financial shape.What about age?The most common rebuttal to what I've presented so far is likely that we're living longer today than we were in the past. So, even if retirees have higher incomes and more security today, they need it because they have to finance a longer retirement.

There is some truth to this, but probably less than many assume.

While there has been tremendous progress in life expectancy over the last century, most of the gains have come to the young.

According to the Centers for Disease Control's actuary tables, someone born in 1950 could expect to live to age 68.2, while someone born in 2010 could expect to live to 78.7.

That's extraordinary: An extra decade of life expectancy gained inside of two generations.

But the gains have been much smaller for those who survive into their retirement years. A 65-year-old in 1950 could expect to live 14 more years, while a 65-year-old in 2010 could expect to live another 19 years. The gains continue to diminish from there. A 75-year-old in 1980 (the earliest we have data on for that age group) could expect 10.4 more years of life. Today, they can expect another 12 years -- a gain of a mere 1.6 years.

Just like the good old days

Let me clearly state what these statistics do not show. They do not show that Americans are prepared for retirement, or that there is no retirement crisis.

There is a retirement crisis.

But there always has been one.

The lack of savings is a grim problem that will affect millions of Americans for decades to come.

But that's nothing new.

Most retirees will have to cut back on their standard of living.

But they always have.

Many will be reliant on Social Security.

But that's been the case for decades.

"When all is said and done," Adams writes, "we're all still challenged to find the combination of funding -- Social Security, personal savings, and employment-based retirement programs -- to provide for a financially satisfying retirement."

"Just like in the 'good old days.'"

Check back every Tuesday and Friday for Morgan Housel's columns on finance and economics.

The Biggest Retirement Myth Ever Told