1st pub. by CV on 08.20.12

By Seth Rosenfeld

Video: Ariane Wu

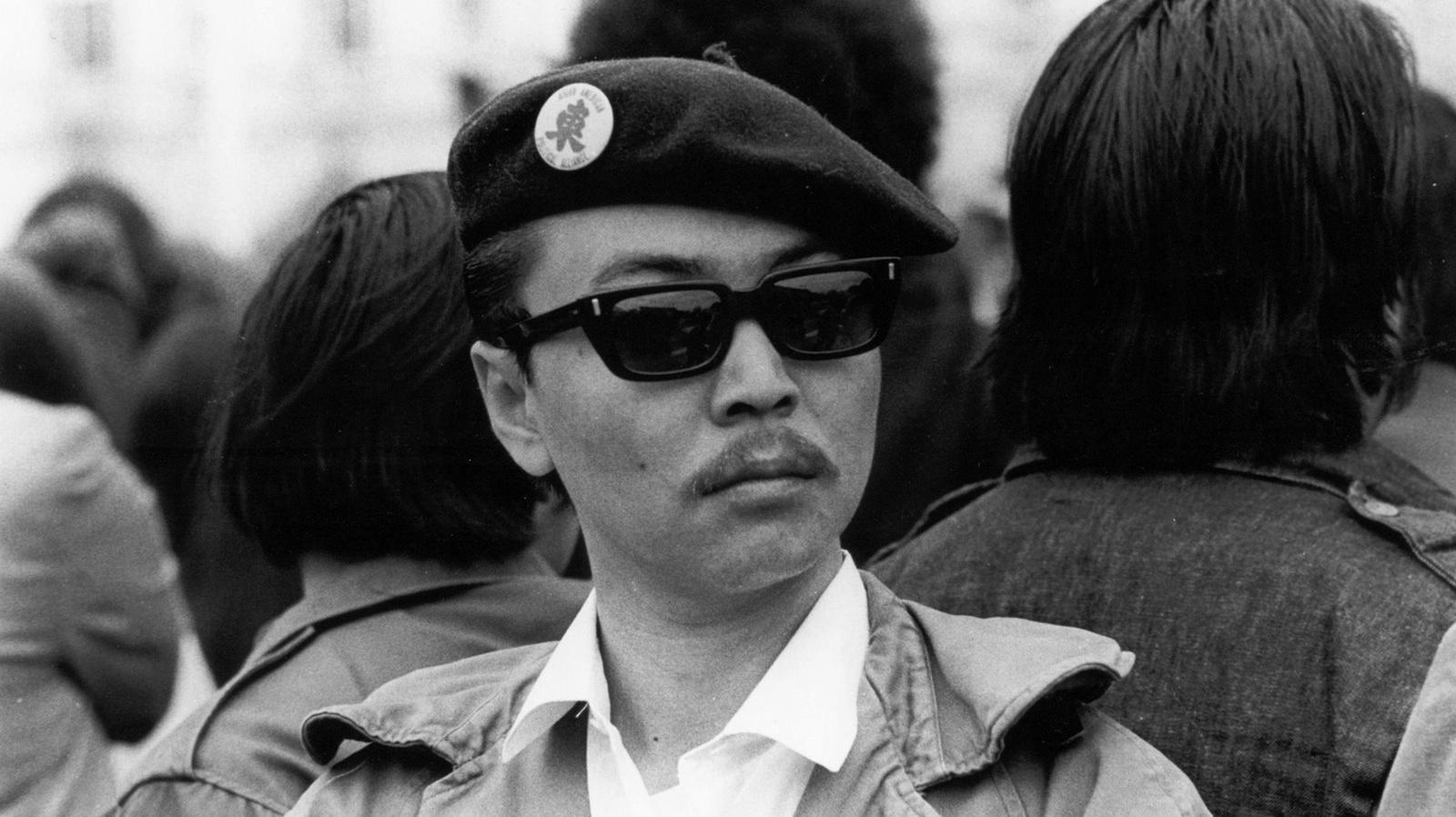

Read full transcript The man who gave the Black Panther Party some of its first firearms and weapons training – which preceded fatal shootouts with Oakland police in the turbulent 1960s – was an undercover FBI informer, according to a former bureau agent and an FBI report. One of the Bay Area’s most prominent radical activists of the era, Richard Masato Aoki was known as a fierce militant who touted his street-fighting abilities. He was a member of several radical groups before joining and arming the Panthers, whose members received international notoriety for brandishing weapons during patrols of the Oakland police and a protest at the state Legislature. Aoki went on to work for 25 years as a teacher, counselor and administrator at the Peralta Community College District, and after his suicide in 2009, he was revered as a fearless radical. But unbeknownst to his fellow activists, Aoki had served as an FBI intelligence informant, covertly filing reports on a wide range of Bay Area political groups, according to the bureau agent who recruited him. That agent, Burney Threadgill Jr., recalled that he approached Aoki in the late 1950s, about the time Aoki was graduating from Berkeley High School. He asked Aoki if he would join left-wing groups and report to the FBI.

Aoki is listed in an FBI report on the Black Panther Party as an “informant” with the code number “T-2.”

The former agent said he asked Aoki how he felt about the Soviet Union, and the young man replied that he had no interest in communism. “I said, ‘Well, why don’t you just go to some of the meetings and tell me who’s there and what they talked about?’ Very pleasant little guy. He always wore dark glasses,” Threadgill recalled. Aoki’s work for the FBI, which has never been reported, was uncovered and verified during research for the book, “Subversives: The FBI’s War on Student Radicals, and Reagan’s Rise to Power.” The book, based on research spanning three decades, will be published tomorrow by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. In a tape-recorded interview for the book in 2007, two years before he committed suicide, Aoki was asked if he had been an FBI informant. Aoki’s first response was a long silence. He then replied, “ ‘Oh,’ is all I can say.” Later during the same interview, Aoki contended the information wasn’t true. Asked if this reporter was mistaken that Aoki had been an informant, Aoki said, “I think you are,” but added: “People change. It is complex. Layer upon layer.” However, the FBI later released records about Aoki in response to a Freedom of Information Act request. A Nov. 16, 1967, intelligence report on the Black Panthers lists Aoki as an “informant” with the code number “T-2.” An FBI spokesman declined to comment on Aoki, citing litigation seeking additional records about him under the Freedom of Information Act. Since his death – Aoki shot himself at his Berkeley home after a long illness – his legend has grown. In a 2009 feature-length documentary film, “Aoki,” and a 2012 biography, “Samurai Among Panthers,” he is portrayed as a militant radical leader. Neither mentions that he had worked with the FBI. Harvey Dong, who was a fellow activist and close friend, said last week that he had never heard that Aoki was an informant. “It’s definitely something that is shocking to hear,” said Dong, who was the executor of Aoki’s estate. “I mean, that’s a big surprise to me.” Dong recalled that Aoki tended to “compartmentalize” the different parts of his life. Before he shot himself, Dong said, Aoki had laid out in his apartment two neatly pressed uniforms: One was the black leather jacket, beret and dark trousers of the Black Panthers. The other was his U.S. Army regimental. In Berkeley in the late 1960s, Aoki wore slicked-back hair, sported sunglasses even at night and spoke with a ghetto patois. His fierce demeanor intimidated even his fellow radicals, several of them have said. “He had swagger up to the moon,” former Berkeley activist Victoria Wong recalled at his memorial. From gangs to the military Aoki was born in San Leandro in 1938, the first of two sons. He was 4 when his family was interned at Topaz, Utah, with thousands of other Japanese Americans during World War II. After the war, Aoki grew up in West Oakland, in an area that had been known as Little Yokohama before becoming a low-income black community. He joined a gang and became a tough street fighter who as an adult would boast, “I was the baddest Oriental come out of West Oakland.” He shoplifted, burgled homes and stole car parts for “the midnight auto supply business,” he told Berkeley’s KPFA radio in a 2006 interview. Oakland police repeatedly arrested him for “mostly petty-type stuff,” he said in the 2007 interview. Still, he graduated from Herbert Hoover Junior High School as co-valedictorian. But the internment during World War II had shattered his family, Aoki had said. His father became a gangster and abandoned his family, and his mother won custody of her sons and moved them to Berkeley. Aoki did well academically at Berkeley High School and became president of the Stamp and Coin Club. However, he assaulted another student in the hallway and, as he recalled, “beat him half to death.” Aoki said he had hoped to become the army’s first Asian American general, but he served only about a year on active duty and seven more in the reserves before being honorably discharged as a sergeant. Although he saw no combat, he became a firearms expert. “I got to play with all the toys I wanted to play with when I was growing up,” he told KPFA. “Pistols, rifles, machine guns, mortars, rocket launchers.” Being in the reserves left Aoki a lot of free time, and he became deeply involved in left-wing political organizations at the behest of the FBI, retired FBI agent Threadgill said during a series of interviews before his death in 2005. “The activities that he got involved in was because of us using him as an informant,” he said. Threadgill recalled that he first approached Aoki after a bureau wiretap on the home phone of Saul and Billie Wachter, local members of the Communist Party, picked up Aoki talking to fellow Berkeley High classmate Doug Wachter. At first, Aoki gathered information about the Communist Party, Threadgill said. But Aoki soon focused on the Socialist Workers Party and its youth affiliate, the Young Socialist Alliance, also targets of an intensive FBI domestic security investigation.Read more>>Man who armed Black Panthers was FBI informant, records show |